Anarcha-feminizm i anarcho-machismo w Hiszpanii (2013)

Wywiad

z the Valeries przeprowadził Jeremy Kay

“Artykuł ten jest

edytowaną wersją wywiadu z grudnia 2012 roku. Pochodzi ze zbioru

tekstów (opublikowanych w ostatnim wydaniu Mutiny), które dotyczą: kryzysu

gospodarczego w Hiszpanii, masowych ruchów społecznych (takich jak “15M")

oraz anarchistycznej polityki. Wywiad ten skupia się na anarcha-feministycznej

perspektywie oraz organizacji. The Valeries są dwiema radykalnymi anarcha-feministkami,

żyjącymi na skłotach w Madrycie. Wywiad został przeprowadzony w języku

hiszpańskim.

- Przepraszam za ewentualne błędy, które mogłem

zrobić z powodu niezrozumienia tekstu lub złego tłumaczenia. - Jeremy.

Historia z Casa Blanca

Zaczniemy

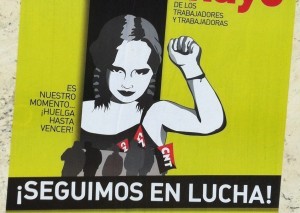

od historii ilustrującej problemy, z którymi anarcha-feministki regularnie

zmagają się w ramach ruchu anarchistycznego w Hiszpanii.

Działo

się to w Casa Blanca - zeskłotowanym, samorządowym centrum społecznym w

Madrycie. Był to duży budynek, który kierowany był zgodnie z mniej lub bardziej

anarchistycznymi zasadami. Został zeskłotowany na początku 2010 roku,

eksmitowany we wrześniu 2012. Setki różnych kolektywów uczestniczyły w

tworzeniu tej przestrzeni. Niedługo po zeskłotowaniu grupa kobiet poprosiła

zgromadzenie ogólne budynku o wydzielenie autonomicznej przestrzeni dla kobiet.

[Artykuł ten stosuje termin

"autonomiczne". Pojęcie używane w języku hiszpańskim znaczy dosłownie

"nie mieszane".] Po przychylnym rozpatrzeniu wniosku przez

zgromadzenie kobiety zaczęły odnawiać przestrzeń, sprzątać, montować

oświetlenie itd.

“W trakcie remontu powiesiłyśmy plakat na

drzwiach pomieszczenia mówiący "autonomiczna przestrzeń - żadnych

machistas ". Ktoś dopisał na plakacie “ani feminazis”. Była to zapowiedź

przyszłych wydarzeń.

Czas mijał, nastąpiły zmiany w kolektywie.

Niektóre z nas zaczęły przygotowywać miejsce do wykorzystania pod kilka nowych

projektów, takich jak siłownia i warsztaty na temat zdrowia. Wysłałyśmy e-mail

do głównej grupy z prośbą o klucz tak, abyśmy mogły wchodzić, kiedy chcemy.

Wszystkie kolektywy miały swój własny klucz. Odpowiedzieli, że mamy udać się na

zgromadzenie z prośbą o przestrzeń. Zdenerwowało nas to, ponieważ nie

sądziłyśmy, aby było to konieczne - przestrzeń była autonomiczna, a

przygotowania już się rozpoczęły. Powiedziałyśmy jednak ok.

"Zgromadzenie" było farsą. Składało się

tylko z dwóch chłopaków z centrum społecznego. To nie było pełne zgromadzenie,

raczej "komisja powitalna". Ludzie przychodzili z propozycjami, a

tych dwóch mówiło, co myśli. Nie był to zbyt demokratyczny sposób podejmowania

decyzji. Wszystkie pozostałe wnioski zostały zaakceptowane. Byłyśmy ostatnie.

Ci dwaj nie rozumieli, co oznacza autonomiczna przestrzeń oraz nie wiedzieli,

że została ona już zagospodarowana w ten sposób. Nie wiedzieli również o pracy,

którą już wykonałyśmy. Wyjaśniłyśmy więc (raz jeszcze - tak jak robimy od 1960

roku!) rozumowanie stojące za autonomiczną przestrzenią. Oznajmili, że nie mogą

teraz podjąć decyzji oraz że może jakaś inna grupa chciałaby tę przestrzeń.

Powiedziałyśmy, że przestrzeni używamy od dawna i nikt jej nie chce. Odparli,

że przekażą wniosek zgromadzeniu i w ciągu tygodnia dostaniemy odpowiedź.

Cóż, czekałyśmy tydzień, dwa, trzy tygodnie,

miesiąc i wciąż nie dostawałyśmy odpowiedzi. Wysłałyśmy więc email z pytaniem,

czy pamiętają o nas i czy decyzja została podjęta, jednak odpowiedzi nie

otrzymałyśmy. Jedna z nas zapisana była na wewnętrzną listę mailową centrum

społecznego, na której zobaczyła e-mail mówiący o tym, że przestrzeń, którą

chciałyśmy zagospodarować, została przydzielona innej, nie autonomicznej

grupie. Wkurzyłyśmy się!

Od tego czasu e-maili już nie wysyłałyśmy.

Zamiast tego napisałyśmy komunikat do wewnętrznej grupy centrum społecznego

oraz zrobiłyśmy małe plakaty do powieszenia w centrum pokrótce wyjaśniające

całą sprawę oraz nasz pogląd na Casa Blanca jako patriarchalną przestrzeń,

nierozumiejącą polityki genderowej. Plakaty powiesiłyśmy w dniu drugiej

rocznicy powstania skłotu. Wielu ludzi patrzyło na nas złowrogo, jednak nie

zadawali żadnych pytań. Jedna z kobiet zaczęła nas obrażać, a dwie inne

zapytały, co się dzieje. Wyjaśniłyśmy, a one na to, że porozmawiają z

chłopakami z komitetu powitalnego. Powiedzieli im (nie nam), że to pomyłka a

plakaty powinny zostać usunięte. Dowiedziałyśmy się potem, że tych dwóch z

komitetu powitalnego nigdy nie przekazało naszego wniosku, po prostu go

zignorowali. Tłumaczyli się, że zapomnieli.

Później otrzymałyśmy e-maile z obelgami. Pisali,

że sabotujemy centrum społeczne oraz że siejemy ferment wśród ruchu i

powinnyśmy się wynosić ze skłotu.

O anarchizmie i

machismo

Wielu ludzi nazywa

siebie "anarchistami". Ale jak rozumiemy to, że ktoś jest

"anarchistą"? Czy jest to ktoś cechujący się pewną estetyką - ktoś

kto nosi kilka znaczków? Czy jest to ktoś, kto rzeczywiście poddaje refleksji

wartości takie jak patriarchat, klasa, rasa i seksualność, które dotyczą

społeczeństwa i nas samych? Zabawne, że gdy nazwiesz niektórych z

anarchistów “machista” obrażają się i nic z tym nie robią; kiedy nazwiesz ich

rasistami, nagle stają się poważni i zaczynają myśleć. Uczciwość jest dla mnie

bardzo ważna. Jeśli naprawdę jesteś anarchistą, podejmiesz próbę autorefleksji,

gdy jesteś poddany krytyce. Nie pozwól, aby duma przyćmiła ci obraz. Duma macho

jest bardzo silna. Generalnie należy się tego spodziewać, niemniej jest to

smutne, kiedy doświadczasz jej od anarchistów. Co więcej, anarchiści częściej

niż inni obrażają się, jeśli podda się ich zachowanie krytyce. To, że nazwiesz

się anarchistą, nie oznacza, że w magiczny sposób stajesz się wspaniały i nie

musisz się zmieniać. W rzeczywistości, nowe pomysły są zawsze trudne do

zaakceptowania.

Wielu ludzi nazywa

siebie "anarchistami". Ale jak rozumiemy to, że ktoś jest

"anarchistą"? Czy jest to ktoś cechujący się pewną estetyką - ktoś

kto nosi kilka znaczków? Czy jest to ktoś, kto rzeczywiście poddaje refleksji

wartości takie jak patriarchat, klasa, rasa i seksualność, które dotyczą

społeczeństwa i nas samych? Zabawne, że gdy nazwiesz niektórych z

anarchistów “machista” obrażają się i nic z tym nie robią; kiedy nazwiesz ich

rasistami, nagle stają się poważni i zaczynają myśleć. Uczciwość jest dla mnie

bardzo ważna. Jeśli naprawdę jesteś anarchistą, podejmiesz próbę autorefleksji,

gdy jesteś poddany krytyce. Nie pozwól, aby duma przyćmiła ci obraz. Duma macho

jest bardzo silna. Generalnie należy się tego spodziewać, niemniej jest to

smutne, kiedy doświadczasz jej od anarchistów. Co więcej, anarchiści częściej

niż inni obrażają się, jeśli podda się ich zachowanie krytyce. To, że nazwiesz

się anarchistą, nie oznacza, że w magiczny sposób stajesz się wspaniały i nie

musisz się zmieniać. W rzeczywistości, nowe pomysły są zawsze trudne do

zaakceptowania.

Dydaktyczna rola, jaką zobowiązane jesteśmy grać,

jest paradoksalna. Oczekuje się od nas bycia słodkimi, cierpliwymi, spokojnymi,

wyrozumiałymi i opiekuńczymi. Ponieważ jest to rola stworzona przez

patriarchat, musimy z nią walczyć. To nie znaczy, że nigdy nie będę dbająca, po

prostu nie cały czas. Ale gdy anarchiści wokół mnie nie rozumieją idei

feministycznych, oczekują, że będę opiekuńcza, kochająca i że wyjaśnię im

wszystko - złości mnie to. Feminizm nie jest specjalnie nowym ruchem i jako

anarchiści powinni mieć jakiekolwiek pojęcie o nim. Problemem dla mnie

jest podejście niektórych ludzi - uważają, że mieszkanie na skłotach i noszenie

bluzy z kapturem czyni z nich anarchistów. Jeśli to wszystko czym dla Ciebie

jest anarchizm, to nie oczekuję, że będziesz chciał rozwijać się ideologicznie.

Gdyby ci, którzy nazywają siebie "anarchistami", naprawdę

sprzeciwialiby się wszelkim formom hierarchii, nie musiałybyśmy nazywać siebie

"radykalnymi anarcha-feministkami", wystarczyłoby

"anarchistki". Ale ponieważ termin "anarchizm" jest źle

używany (tylko jako pewna moda) traci swoje znaczenie.

Niektórzy z anarchistów uważają, że feminizm oraz

anarchizm powinny zostać rozdzielone. Uważają feminizm za zinstytucjonalizowaną

walkę reformistyczną. Nie widzą mnogości nurtów w obrębie feminizmu. Uważamy,

że taka perspektywa to tylko pretekst, aby uniknąć podejmowania feministycznych

działań.

O

anarcha-feminizmie w Hiszpanii

Anarcha-feministyczny ruch w Hiszpanii jest

całkiem dobrze zorganizowany. Prowadzimy dyskusje oraz warsztaty dotyczące

takich problemów jak przemoc oraz agresja na tle płciowym, role genderowe oraz

autorytaryzm. Pomysły oraz akcje często mają swój początek na tych spotkaniach,

pomimo że odległości, które nas dzielą, bywają problematyczne. Mamy luźną sieć

kontaktów z ludźmi na Półwyspie Iberyjskim, którzy, podobnie jak my, myślą o

gender.

Jednym z często dyskutowanych problemów jest to,

jak wykroczyć poza samoobronę. Tak wiele naszej energii skierowane jest na

mężczyzn, włączając w to potrzebę tłumaczenia feminizmu przez cały czas.

Oczywiście, chcemy być inkluzywne wobec męskich towarzyszy w walce, ale nie

kosztem siebie. Oni też muszą podjąć próbę zrozumienia, jak mają się

zachowywać, kształcić oraz poddawać autokrytyce. To nie jest nasza

odpowiedzialność. Musimy skupić swój czas i energię na sobie, dla siebie. Jeśli

nie, nie uda nam się poszerzyć działalności. Nie chcemy, spędzać całego naszego

czasu na usprawiedliwianiu i legitymizowaniu tego co robimy. To wpływa na nas -

to wpływa na naszą wiarę w siebie.

Ważne jest, aby spędzać trochę czasu w

autonomicznych kobiecych grupach. To pomaga, w postrzeganiu mieszanych grup

oraz genderowych konstrukcji w nowy sposób. Gęsta sieć autonomicznych kobiecych

przestrzeni istnieje w Madrycie i innych częściach Hiszpanii. Spędzałyśmy czas,

pracując z samymi kobietami oraz z mężczyznami, jednak zawsze byłyśmy nazywane

"feminazistkami"! To jeden z powodów, dla których autonomiczne

przestrzenie są potrzebne, pozwalają uciec od machismo.

Chcemy również, aby termin "feministka"

był inkluzywny dla osób transseksualnych. Feminizm rozwija się cały czas i

dzisiaj koncepcja "kobiety" nie pasuje tak dobrze. Nie zawiera w

sobie lesbijek oraz osób transseksualnych. Autonomiczne przestrzenie otwarte są

dla trans-womyn.* Staramy się również używać języka w sposób rzucający wyzwanie

patriarchatowi. Na przykład używamy kobiecej formy, mówiąc w liczbie mnogiej

(zamiast męskiej postaci, która jest zwykle używana w języku hiszpańskim). [W tym artykule, pisownia 'womyn' używana jest jako

niedoskonały sposób odzwierciedlenia niektórych feministycznych działań

językowych używanych przez the Valeries w języku hiszpańskim.]

Nazywamy siebie "radykalnymi

anarcha-feministkami", ponieważ wiele osób określa siebie

"anarcha-feministkami", nie potrafiąc krytykować patriarchatu. Wydaje

nam się, że włożyłyśmy wiele wysiłku oraz refleksji w rozwijanie naszej krytyki

patriarchalnych wartości. Uważamy, że u podstawy [root] problemu leży

patriarchat, dlatego też nazywamy siebie "radykalnymi"[radica],

ponieważ określenie to wywodzi się od słowa "root".

Radykalny anarcha-feminizm jest dobrą postawą,

ponieważ polega na wprowadzaniu zmian teraz. Niektórzy/które twierdzą, że

"to nie jest ten czas". Jednak radykalne anarcha-feministki

odpowiadają - nie będziemy czekać aż świat zrozumie, musimy działać teraz,

musimy unikać bycia ofiarami.

O feministycznym

ruchu reformistycznym

W obszernym ruchu 15M, istnieje grupa

"Feminista Sol". To zgromadzenie i nominalnie feministyczna część

15M. Z jednej strony lubimy je, z drugiej obawiamy się go. Podkreśla

kwestie feminizmu i patriarchatu - bardzo ważne działanie w tym społeczeństwie

- ma jednak bardzo reformistyczny charakter, jak całe 15M. Strategia zwracania

się do państwa o wprowadzanie zmian prowadzi do utraty autonomii. To absurd -

nie możemy walczyć z państwem jednocześnie prosząc je o reformy. Przypomina to

Międzynarodowy Dzień Kobiet: dostajemy pozwolenie, aby podczas jednego dnia

wyjść na ulice i krzyczeć, pozostałą część roku mamy siedzieć cicho. Wszystkie

partie w nim uczestniczą. To śmieszne.

Za podobnie problematyczną uważamy legalizację

aborcji. [W Hiszpanii aborcja jest legalna od

2010 roku - z pewnymi ograniczeniami. Wcześniej aborcja nie była karana, ale

nie była również legalna i aby ją wykonać kobieta musiała udowodnić istnienie

"poważnego zagrożenia dla zdrowia fizycznego lub psychicznego".]

Niektóre anarcha-feministki brały udział w kampanii na rzecz legalizacji

aborcji, tak samo jak feministki, które nie były anarchistkami. Uważamy jednak,

że niebezpiecznym jest prosić o prawa, które w efekcie dają państwu jeszcze

więcej władzy. Kontrola nad własnymi ciałami jest odpowiedzialnością, którą

musimy podjąć same.

Autor: Jeremy Key

Źródło: mutinyzine.blog.com

Korekta: Miśka

Tłumaczył: Jakuszek

ORYGINAŁ

We’ll start with a story that illustrates the sort of thing anarcha-feminists regularly deal with within the anarchist movement in Spain.A story from Casa Blanca

The didactic role that we are required to play is one of the paradoxes. Because one of the roles you have to assume as a womyn is to be sweet, patient, calm, understanding and caring. As this is a role created by patriarchy, we have to fight against it. This doesn’t mean that I’ll never be caring, just not all the time. But when anarchists around me don’t understand feminist ideas, they expect me to be caring and lovely and explain things to them. But I get angry – since the ideas of feminism aren’t exactly new, and if they’re anarchists, they should have some idea of them! For me it’s a problem here that as soon as a person squats and wears a hoodie and dumpster-dives, they consider themselves an anarchist. If that’s all anarchism means to you, then you don’t feel like you need to develop any deeper political ideas. If those who call themselves ‘anarchist’ truly opposed all hierarchies, we wouldn’t need to call ourselves ‘radical anarcha-feminists’, just ‘anarchists’. But because the term ‘anarchism’ is used poorly, and just as a fashion, it loses its meaning.There are many people here who call themselves ‘anarchist’. But how do we understand who is an ‘anarchist’? Is it someone with a certain aesthetic – who wears a few badges, or is it someone who actually reflects on the values of patriarchy, class, race and sexuality that exist in society and within ourselves? It’s funny that when you call some anarchist ‘machista’, they get all offended, and don’t look within themselves. Whereas if you point out when someone is being racist, they take it seriously and look within. For me honesty is very important. If you really are an anarchist, you will look within when you are criticised. You won’t let your pride get in the way. The macho pride here is very strong. This is to be expected in general, but it’s sad when you find it among anarchists. In fact, often anarchist boys take greater offence if they’re called out on their behaviour, than non-anarchist boys. Because of course, as soon as you call yourself ‘anarchist’, you’re a mountain of marvellous things, and don’t need to change. In reality, new ideas are always difficult to accept.

Similarly, we think the demand to legalise abortion is very problematic. [In Spain abortion has been legal since 2010 – with some procedural restrictions. Before that it was decriminalised but not legal and womyn had to prove 'serious risk to physical or mental health'.] Some anarcha-feminists have participated in campaigning for the legalisation of abortion, as well as feminists who are not anarchists of course. But we think it is dangerous to ask for more laws which end up delegating more of our own power to the State. Control over our own bodies is a responsibility that we need to assume ourselves.on the other, it makes us afraid. It highlights the issues of feminism and patriarchy – a very important action in this society – but it has a very reformist character, like 15M in general. The strategy is all about asking the State for things, which leads to a loss of autonomy. It’s absurd – we can’t ask the State for things and at the same time fight against it. It’s like the International Women’s Day rally: the one day when we’re given permission to go on the street and shout – and the rest of the time we have to shut up. All of the political parties participate in the rally. It’s ridiculous.

ORYGINAŁ

Interview with the Valeries by Jeremy Kay

This article is an edited interview from December 2012. It follows on from a set of interviews (published in the last edition of Mutiny) which discussed Spain’s economic crisis, massive social movements (such as ’15M’), and anarchistic politics. This interview focusses on anarcha-feminist organising and perspectives. The Valeries are two radical anarcha-feminist squatters living in Madrid. The interview was conducted in Spanish – I apologise for any errors I may have made due to misunderstandings or poor translation. – Jeremy.

We’ll start with a story that illustrates the sort of thing anarcha-feminists regularly deal with within the anarchist movement in Spain.A story from Casa Blanca

It happened at Casa Blanca – a squatted, self-managed social centre in central Madrid. It was a very big building with lots of space, and had more-or-less anarchist politics. It was squatted in early 2010 and evicted in September 2012. Hundreds of different collectives participated in the space.

Sometime towards the beginning of the occupation, a group of womyn asked the general assembly of the building for a womyn’s autonomous space. [This article uses the term 'autonomous' as is common among English-speaking activists, but the term used in Spanish is literally 'non-mixed'.] The assembly said yes to this request, and the womyn started fixing up the space – cleaning and putting in lights etc.

During this time, we put up a poster on the door of the space that said ‘autonomous space – no machistas’ [ie 'no patriarchs / macho arseholes']. Someone wrote on the poster underneath ‘nor feminazis.’ That was a sign of things to come.

There were some changes in the collective and time passed, and then a group of us started to prepare the space to be used for some new things like a gym and workshops on self-managed health.

We sent an email to the main group to ask for a key so that we could enter at will. All the collectives had their own key. They responded that we had to go to an assembly to ask for the space. We flipped out a bit at this, since we didn’t think it was necessary, as the space was autonomous, and that process had already happened anyway. But we said OK, fine.

But the ‘assembly’ was a joke. There were only two guys from the social centre – it wasn’t a full assembly, but rather a ‘welcoming committee’. Other people brought proposals, and the two guys said what they thought. It wasn’t a very horizontal way of making decisions! All the other proposals were accepted. We were last. The two guys didn’t understand what an autonomous space was, and didn’t know that the space had already been designated as such. They also didn’t know about the work that we had already done. So we explained (yet again – as we’ve been doing since the 1960s!) the reasoning behind autonomous spaces. They said they couldn’t decide on the spot, and maybe another group wanted the space. We said that we knew no-one else wanted it because we’d been there a lot, using it. But they said that they would pass the proposal to the assembly and that in a week there would be a response.

Well, we waited a week, then two weeks, three weeks, one month, and still there was no response. So we sent an email asking if they remembered us and if they’d made a decision. They didn’t respond. But one of us was on the internal email list for the social centre and saw an email that said the space was going to be used for a different group, a non-autonomous group. We were pretty pissed at that!

From then on we didn’t send emails obviously. Instead we wrote a communique to the internal group of the social centre. We also did some small posters to put up in the social centre in which we explained briefly what had happened and that we considered Casa Blanca to be a patriarchal space with a lack of understanding of gender politics. We went to put up the posters on the day of the 2 year anniversary when it was full of people. Many people looked at us in a malicious way, but didn’t ask us anything when we put the posters up. One womyn started insulting us, and two others asked what was happening. We told them the story, and they said they would talk with the guys from the welcoming committee, who then said to them (not us) that it had been a mistake, and so we should take down the posters. We found out later that those two guys from the welcoming committee had never passed on our proposal, they had just ignored it. According to them, they had forgotten.

Later we received emails with insults that we were sabotaging the social centre and ‘fragmenting the movement’, and that we should get lost.

On anarchism and machismo

The didactic role that we are required to play is one of the paradoxes. Because one of the roles you have to assume as a womyn is to be sweet, patient, calm, understanding and caring. As this is a role created by patriarchy, we have to fight against it. This doesn’t mean that I’ll never be caring, just not all the time. But when anarchists around me don’t understand feminist ideas, they expect me to be caring and lovely and explain things to them. But I get angry – since the ideas of feminism aren’t exactly new, and if they’re anarchists, they should have some idea of them! For me it’s a problem here that as soon as a person squats and wears a hoodie and dumpster-dives, they consider themselves an anarchist. If that’s all anarchism means to you, then you don’t feel like you need to develop any deeper political ideas. If those who call themselves ‘anarchist’ truly opposed all hierarchies, we wouldn’t need to call ourselves ‘radical anarcha-feminists’, just ‘anarchists’. But because the term ‘anarchism’ is used poorly, and just as a fashion, it loses its meaning.There are many people here who call themselves ‘anarchist’. But how do we understand who is an ‘anarchist’? Is it someone with a certain aesthetic – who wears a few badges, or is it someone who actually reflects on the values of patriarchy, class, race and sexuality that exist in society and within ourselves? It’s funny that when you call some anarchist ‘machista’, they get all offended, and don’t look within themselves. Whereas if you point out when someone is being racist, they take it seriously and look within. For me honesty is very important. If you really are an anarchist, you will look within when you are criticised. You won’t let your pride get in the way. The macho pride here is very strong. This is to be expected in general, but it’s sad when you find it among anarchists. In fact, often anarchist boys take greater offence if they’re called out on their behaviour, than non-anarchist boys. Because of course, as soon as you call yourself ‘anarchist’, you’re a mountain of marvellous things, and don’t need to change. In reality, new ideas are always difficult to accept.

There’s also a perspective among some anarchists here, that separates anarchism and feminism. They see feminism as an institutionalised, reformist fight. They don’t see the strands within feminism. We think this perspective is just an excuse to avoid working on any feminist actions.

On the anarcha-feminist movement in Spain

In general, the anarcha-feminist movement in Spain is quite well connected. We put on talks and workshops about issues such as gendered violence and aggression, gender roles and authoritarianism. Proposals and actions often arise out of these events, although distance is a problem for us. We have a loose network across the Iberian peninsula of people who have a good perspective on gender.

One idea that we’ve been discussing a lot is about how to move on beyond self-defense. So much of our energy is directed at men. And this includes having to explain feminist ideas to them all the time. Sure, we want to include male comrades in the struggle, but not at the cost of ourselves. They also have to take steps and realise how to act, how to educate themselves, how to critique themselves. This isn’t our responsibility. We need to employ our time and energy on ourselves, for ourselves. If not, we can’t advance. We don’t want to spend our whole time justifying and legitimising ourselves. This affects us – it affects our ability to believe in ourselves.

It’s important to spend some time in womyn’s autonomous groups. It helps to be able to come back to mixed groups and see them in a new way, to see the gendered constructions. A strong network of womyn’s autonomous spaces exists in Madrid and other parts of Spain. We’ve spent time working just with womyn, and time working with men – either way we get called ‘feminazis’! This is one reason why we need autonomous groups – to be away from this sort of machismo.

We also want the term ‘feminist’ to include the trans reality. Feminism is advancing all the time and nowadays the concept of ‘woman’ doesn’t fit so well – it doesn’t include the ideas of lesbianism or trans. Trans-womyn are included in our autonomous spaces.

We also attempt to use language in ways that challenge patriarchy. For example we use the feminine form when speaking in the plural (instead of the masculine form which is normally used in Spanish). [In this article, the spelling 'womyn' is used as an imperfect way to reflect some of the feminist linguistic actions used by the Valeries in Spanish.]

We call ourselves ‘radical anarcha-feminists’ because many people here call themselves ‘anarcha-feminists’ without really having the critique of patriarchy. We feel we’ve done a lot of work and personal reflection to develop our critique of the construction of patriachal values. We also consider patriarchy to be one of the roots of the problem – and for this reason we like the term ‘radical’, which originally comes from the word for ‘root’.

We think a radical anarcha-feminist posture is good, because it’s about making change now. Others say ‘it’s not the time’. But radical anarcha-feminists reply that that we’re not waiting until the world understands – we have to act now, whether they understand or not. We have to avoid being victims.

On the reformist feminist movement

Within the broad 15M movement, there exists the group ‘Feminista Sol’. It’s an assembly and nominally the feminist part of 15M. On one hand we like it,

Similarly, we think the demand to legalise abortion is very problematic. [In Spain abortion has been legal since 2010 – with some procedural restrictions. Before that it was decriminalised but not legal and womyn had to prove 'serious risk to physical or mental health'.] Some anarcha-feminists have participated in campaigning for the legalisation of abortion, as well as feminists who are not anarchists of course. But we think it is dangerous to ask for more laws which end up delegating more of our own power to the State. Control over our own bodies is a responsibility that we need to assume ourselves.on the other, it makes us afraid. It highlights the issues of feminism and patriarchy – a very important action in this society – but it has a very reformist character, like 15M in general. The strategy is all about asking the State for things, which leads to a loss of autonomy. It’s absurd – we can’t ask the State for things and at the same time fight against it. It’s like the International Women’s Day rally: the one day when we’re given permission to go on the street and shout – and the rest of the time we have to shut up. All of the political parties participate in the rally. It’s ridiculous.

Brak komentarzy:

Prześlij komentarz